- Fall 2025

Implementation Corner

The Implementation Corner features a specific technology or idea previously tested on the Test Track that was adopted and implemented by a sponsoring agency. Many of these implemented technologies are still producing enormous benefits years later! Part of NCAT’s mission is to facilitate broader implementation of proven technologies into mainstream practice across the USA and abroad.

From default to data-driven design

For decades, pavement design in the United States relied solely on the 1993 AASHTO Pavement Design Guide, which was rooted in the 1958–1960 AASHO Road Test. A key input in this empirical design framework is the structural layer coefficient, a number used to quantify the strength and

load-carrying ability of each pavement layer.

Like most state DOTs, the Alabama DOT adopted 0.44 as its structural coefficient (a1) for all surface and intermediate asphalt layers based on a limited set of pavement and vehicle conditions from the AASHO Road Test. Specifically, the coefficient was determined using a limited number of pavement cross sections, and only one type of subgrade, base, and asphalt pavement type.

Furthermore, only two million ESALs were applied during the AASHO Road Test, and only one type of bias-ply tire, inflated to 70 psi, was used. The combined effect of these limited parameters was a very conservative estimate of the structural contribution of the asphalt layers in a pavement.

The upshot of this conservatism was the high likelihood for over-designed pavement thicknesses. Furthermore, given that the AASHO Road Test was conducted more than 60 years ago, using a layer coefficient established at that time ignores the advancements in materials specifications and construction methods over that time. Consequently, updating the asphalt layer coefficient based on highly validated data from the NCAT Test Track

was expected to lead to more cost-effective pavement designs.

Although previous work had been conducted on improving and refining the knowledge of the effects of specific inputs into the 1993 AASHTO Pavement Design Guide, studies seeking to improve the layer coefficients were especially difficult. Much of the research resulted in findings that were very time-consuming or difficult to implement. Other findings were plagued by high variability or only marginal improvement over the 0.44 value. A few studies suggested that a higher layer coefficient could be safely used, but overall, the concept of changing

the coefficient suffered from a high degree of uncertainty.

A sensitivity analysis conducted by NCAT, led by Dr. David Timm, demonstrated that the layer coefficient was the most influential variable in the 1993 design guide, and thus, it had the highest potential for cost savings. Thus, in 2008, ALDOT partnered with NCAT to further investigate whether the asphalt structural coefficient could be updated.

Putting the Test Track to work

NCAT and ALDOT analyzed more than a dozen different cross sections on the 2003 and 2006 NCAT Test Track cycles. Instead of having a single type of asphalt mix, granular base, and subgrade, these test sections had a variety of base materials and thicknesses, subgrade materials, aggregate types, asphalt binder grades, and mix types. This variety allowed NCAT researchers to experimentally evaluate the sensitivity of the pavement design model to different measured inputs.

IRI data collected using an ARAN van during the 2003 and 2006 research cycles were converted to the present serviceability index (PSI), a pavement performance measure used in the 1993 AASHTO guide to quantify the effects of pavement distress.

The change in PSI over the course of the research cycles was estimated for each test section according to the actual change in measured IRI. This value was input into the AASHTO model along with the properties of the individual test sections to predict the number of equivalent single axle loads (ESALs) necessary to cause the specific change in PSI for each test section. These predictions were compared to the actual applied ESALs to determine the accuracy of AASHTO model. Immediately, NCAT researchers noticed substantial differences between the predicted and actual ESALs.

In some cases, the AASHTO model underpredicted the amount of ESALs by over 60%. In other words, the true quality of the pavements in the test sections was being drastically discounted. For each test section, the layer coefficient was iteratively changed until the relationship between the predicted and actual ESALs over time for each test section was the best fit. The data indicated that 89% of the test sections were over-designed using a structural coefficient of 0.44.

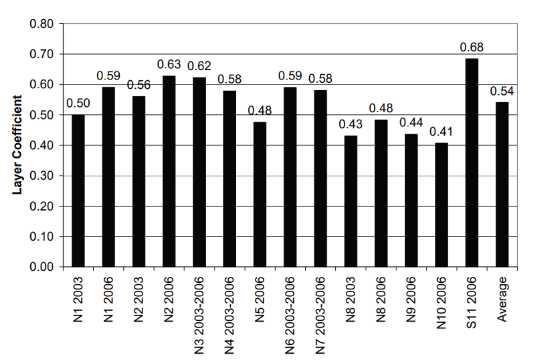

The average layer coefficient from this analysis was 0.54 with a reasonably low standard deviation of 0.08. Furthermore, the average measurement of best-fit, R2, was 76%, which was considered acceptable given the small sample size. Only two test sections had coefficients lower than the original 0.44; these two sections exhibited strong signs of delamination of layers and debonding, leading to the reduced coefficients.

Figure 1. Estimated Layer Coefficients from 2003 and 2006 NCAT Test Sections

Implementing in Alabama

In 2009, ALDOT officially adopted the new structural coefficient of 0.54 into its pavement design procedures. Later work at the NCAT Test Track further validated this change. This single change resulted in an 18% reduction in HMA thickness. Larry Lockett, the ALDOT state materials and test engineer at the time, said, “this means that our resurfacing budget will go 18% farther than it has in the past. We will be able to pave more roads, more lanes, more miles, because of this 18% savings.” Practically, this has allowed ALDOT to be more efficient with tens of millions of dollars every year since this change.

The recalibration represented the first instance in the nation where a state DOT formally updated its asphalt coefficient above the 1993 AASHTO default value. Since then, only the state of Washington has taken a similar step with the 1993 Design Guide, revising its value to 0.50. Although many states have adopted more mechanistic-based pavement design methodologies, the work positioned Alabama as a national leader in data-driven policy updates and strengthened confidence in the NCAT Test Track as a tool for implementation-ready solutions. ALDOT’s investment in this research positioned them to receive an enormous return on investment in the order of $100M that has been used for additional resurfacing projects across the state.

Why it still matters today

Why does this work from over 15 years ago still matter? First, it is worth reminding the asphalt pavement community of benefits of practical and highly-validated research. Second, sometimes old ideas inspire new ideas in new environments. Particularly today, when highly polymer-modified asphalt binders are more prevalent, new innovative mixture additives are constantly being introduced to the market, and construction methods are constantly improving, reevaluating default inputs or the status quo provides opportunities for state agencies to be more efficient with available funding.

Contact Nathan Moore for more information on this research.